I brought my high school literary magazine home to distressingly little fanfare. I placed it on the coffee table, where it sat until my Nana1 came to visit. He found it there, collecting dust, and gave it a read.

“Neha! You are a poet,” he exclaimed, as he shuffled over to me, triumphantly waving the magazine in the air and shaking from it a cascade of confetti. His eyes widened. He looked at me anew and yelled loud enough that my mom could hear, “She is an intellectual AND an artist!”

I mirrored back his awe, wonderstruck at the wholly unfamiliar experience of being seen, championed, and understood. I was stunned by the glory Nana insisted was mine. Skilled at smallness, I found myself unable to claim it.

I think a lot about Nana these days – half-a-lifetime after poetry became too frivolous of an endeavor for a soon-to-be-lawyer. After Nana died, I discovered journals filled with his writing, asking the questions life had left to him and answering the calls of his own inheritance. As it turns out, my Nana was a writer. My Nana was an intellectual AND an artist! And I didn’t know it until he was gone.

I couldn’t truly believe for myself that I was an artist until much of me was gone, lost to severe chronic illness. A decade deep into daily chronic migraine, upon becoming more honest about my illness and needs, I found myself isolated and erased, abandoned by most of my chosen family and some of my actual family. Turns out, when you finally can access truth, most people will flee from it.

The more unseen my suffering, the more unseen became my strengths, and I started to disappear into the abyss.

The more I spoke about my suffering, the less I was heard. Where I sought support, I often found friction, ableist attacks, and quiet indictments of “inconvenience.” Most days, all I had left were my pain and my voice, but my voice kept disappearing into the abyss, as loved ones invalidated it, muted it, or simply ignored it. The more unseen my suffering, the more unseen became my strengths, and I started to disappear into the abyss.

Two summers ago, I had a temporary medical breakthrough and was gifted 31 days of respite in the form of milder migraine attacks. I leapt from the land of the unliving, so moved by this slice of life livable that the poem, “31,” came pouring out of me through the tear-torn canyons in my soul.

31

31 days I lived, you see,

I filled my bags, unfurled my wings, and found

my balance, and the earth was small and I was mighty,

and the noise was enough but no more, and shhhhh…I slept and I dreamt and awoke

to a dawn of possibilities, of maps unmade and winding avenues to Somewheres, and I touched my toes to the ground, strong, and I touched my eyes to the vacant room on the wall of the crowded room, and I cried, oh how I cried, and I ate the stinky food and I drank the stinky wine, and I learned I could drink more, and I remembered what it felt like to want – to want to fill the dishwasher and empty my held breath, to bend down and reach up and bend down again with sweet sweet nothing pulsing through my brain, and then and

then and

then.

And….

In my fresh despair after the 31 glorious days ended, I started reading poetry. As my despair gathered into a storm of depression, I committed to reading one poem a day to buoy myself to beauty. In the bowels of those godless days, I found scripture in the writing of Andrea Gibson and found myself (struggle, strengths, and all!) in their poem, “Gender in the Key of Lyme Disease”: “Good god / there isn’t a healthy body in the world / that is stronger than a sick person’s spirit.”2

Art has become how I make meaning of my life and how life makes meaning of me.

Inspired, I resumed writing, but in this era of my life, using it to unmask pain instead of mask it. I wrote of my worries, “Did you think that if they went unacknowledged, they would disappear? Did you know that if I go unacknowledged, I may disappear?”3

Whereas my multi-marginalization as a disabled, Desi woman had ripped me into pieces, I claimed space for my wholeness through my language: “What is the currency of time? / of justice? / of spoons / I never had because I was / made to be the chamcha4

?”5 I began to combat erasure with my art, asking, “How to know those whose existence has been erased – hidden by the husbands in my family tree? // Half of my roots have been amputated,”6 I discovered that my voice could birth life in the land of the unliving and break generational trauma cycles–saving not just my life, but the lives of my progeny. I wrote of my daughter: “Let me be not her cage, but / her courage. But if I am her / cage, please let her leave it / with me, and I will scatter / seeds where she once slept / and grow something / that is meant to be / eaten.”7

Art has become how I make meaning of my life and how life makes meaning of me. In my art, I finally have a place to express my truth with its unmitigated violence, and through the act of creating it, somehow find mitigation. Finally, like my Nana before me, I am answering the call of my own inheritance. I have found liberation in the form of language, and writing has been my own uncaging. Finally, my pain is poetry.

Footnotes

1. maternal grandfather

2. Gibson, Andrea. Lord of the Butterflies, p. 26.

3. Sampat, Neha. “Letter from the Land of the Unliving,” published in HNDL Magazine’s “Light,” p. 40.

4. “Chamcha” means “spoon” in Hindi, but is slang for a suck‑up or bootlicker, often the position Indians were put in under British colonization. “Spoon” is also English slang for the limited energy of people with chronic illnesses.

5. Sampat, Neha. “In the Red.”

6. Sampat, Neha. “These Softer Spots.”

7. Sampat, Neha. “Leave it with me.”

NEHA M. SAMPAT

As a besharam (shameless) brown, queer, chronically ill woman, Neha M. Sampat centers life on multiple margins through her speaking, writing, creating, advocating, and acting up. They are a mama, box-breaker, recovered people-pleaser, former lawyer, and founder of BelongLab. She works to make community cool again, and you can find her online at @nehainprint on Instagram, and at @nehaunerased on Substack.

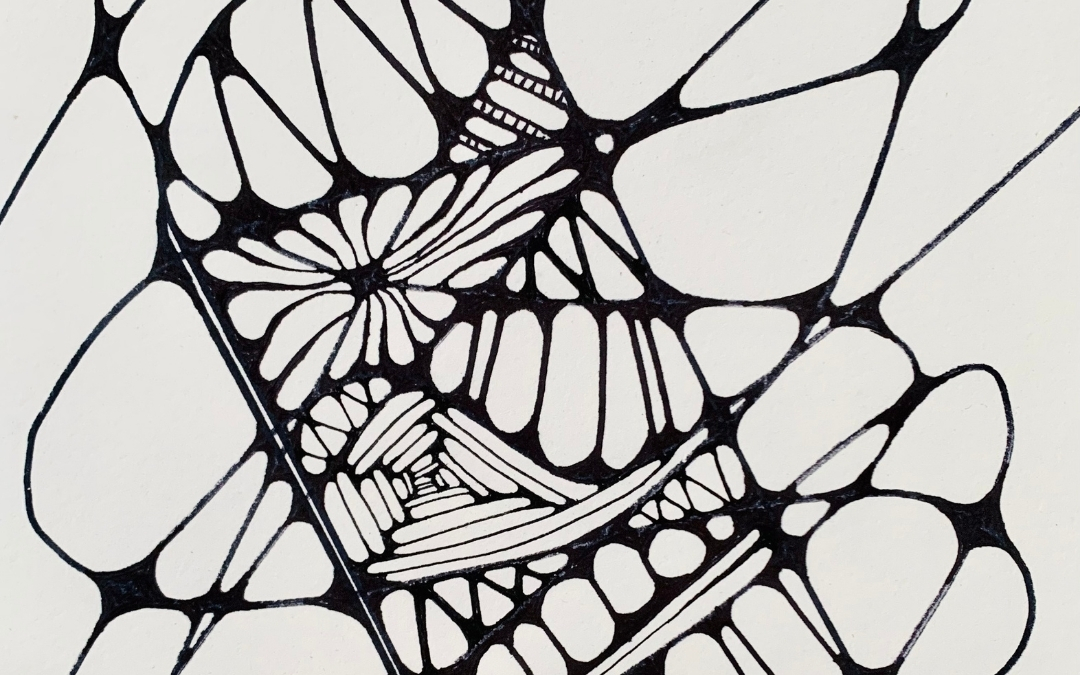

Artwork: Neha M. Sampat, Good Medicine 1, 2023. Marker 5″x7″

Subscribe to our newsletter for early access to Art Saves Lives Essays!

Art Saves Lives by Community Building Art Works is a series of essays where contemporary authors, poets, and artists reflect on the sacred act of art making and allow readers to feel seen and safe to reach further inside of themselves in their own art making practice. To receive these essays in your email before they are available to the wider public, sign up for our newsletter, here.